Liver tumor in gene therapy recipient raises concerns about virus widely used in treatment

4 Years, 3 Months, 3 Weeks, 5 Days, 1 Hour, 13 Minutes ago

It’s troubling news that gene therapy researchers have long anticipated: A hemophilia patient injected with a virus carrying a therapeutic gene in a clinical trial has developed a liver tumor. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has halted the associated clinical trials, and uniQure, the Dutch firm behind the studies, is now investigating whether the virus itself caused the cancer.

Gene therapy experts say that’s unlikely. The patient had underlying conditions that predisposed him to liver cancer. Still, scientists say it’s crucial to rule out any role for adeno-associated virus (AAV), the viral delivery system, or vector, that is used in hundreds of other gene therapy trials. “Everyone will want to know what happened,” says physician-scientist David Lillicrap of Queen’s University, a hemophilia researcher who was not involved with the uniQure study.

Gene therapy for various forms of the blood-clotting disorder hemophilia has been one of the field’s latest success stories. UniQure’s hemophilia B treatment appears to be among the treatments working, with 52 of 54 patients no longer needing injections of factor IX after 6 months in its latest study.

But yesterday, uniQure revealed that an abdominal ultrasound done as part of its ongoing safety monitoring of trial participants found a liver mass in a patient treated in October 2019, prompting FDA to impose a hold on the company’s three hemophilia trials. The news sent uniQure stock plunging, along with shares of other companies working on AAV gene therapy.

Still, there’s reason to believe the virus didn’t cause the cancer. The patient was older, uniQure notes, and he had a liver disease that raises cancer risk. He also became infected with the hepatitis B and C viruses more than 25 years ago. Chronic infections of these viruses are linked to 80% of cases of hepatocellular carcinoma, the type of liver cancer found in the trial participant. But FDA and others are concerned because AAV vectors have produced cancer in mouse studies.

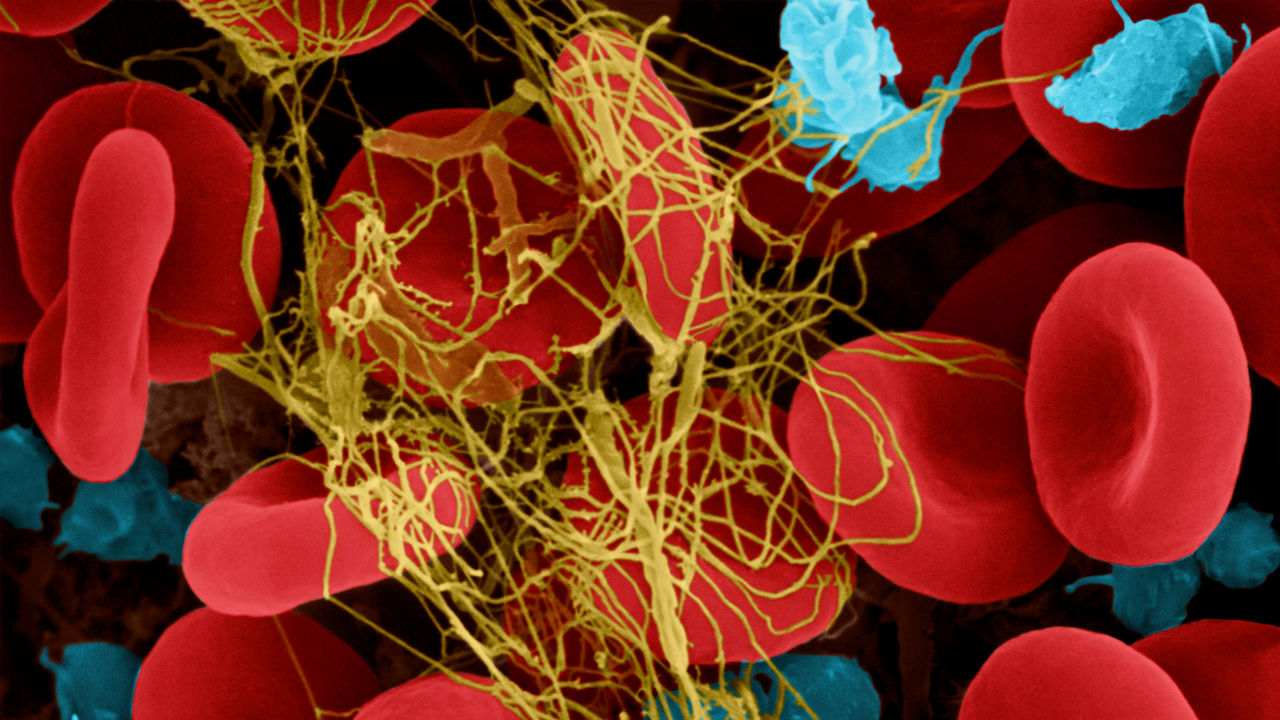

The AAV-delivered DNA normally forms a free-floating loop in the cell’s nucleus. But studies in newborn mice have shown AAV can sometimes integrate its cargo into the recipient’s chromosomes and cause liver cancer. And last year, researchers reported that several dogs treated with AAV for hemophilia A had foreign DNA in chromosome locations that apparently triggered rapid cell growth.

But this was years after the dogs got the therapy, and the animals did not develop tumors. Because the uniQuere patient received the gene therapy relatively recently, it’s “inconceivable” that the AAV was the primary cause of the cancer, Lillicrap says. Still, he adds, if the patient already had a slow-growing liver tumor from his hepatitis infections, the AAV could have inserted into his liver cells’ DNA in a way that spurred faster growth.

To find out whether that happened, uniQure will need to first confirm the tumor is cancerous with a biopsy, then analyze cellular samples for genomic changes. The AAV could be implicated if the tumor is made up entirely of identical cells, or clones, that contain traces of the AAV’s DNA cargo in the cells’ genome near a growth or cancer gene, says Denise Sabatino of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, who led the recently published dog study. “The AAV DNA would need to be found in the exact same site in all cells in the tumor.”

The company expects to complete these studies in the next few months. If the AAV is linked to the cancer, that could raise cancer concerns about other gene therapy treatments using high doses of AAV, especially for older patients who already have liver damage, Lillicrap says.